05_What America’s Best Small Towns Are Getting Right with Deborah and James Fallows

Hosted by Quint Studer with special guests Deborah and James Fallows

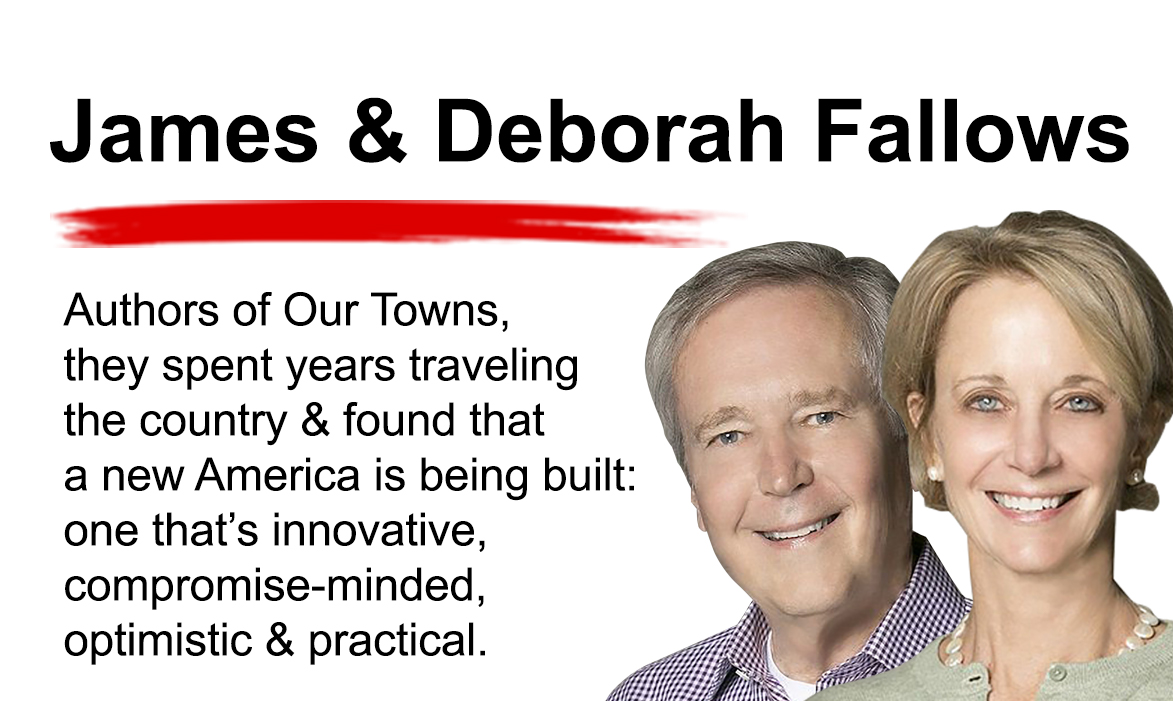

Don’t miss Quint’s delightful conversation with James Fallows and Deborah Fallows, authors of New York Times bestseller Our Towns: A 100,000-Mile Journey into the Heart of America. Their book explores they learned when they hopped on a small plane and visited towns across the country where good things were happening that were not necessarily shown on the evening news. In this podcast they discuss some of these findings, as well as how the COVID pandemic has given communities a greater sense of urgency to fix their issues.

A big point of discussion is the patterns of success Deborah and James see in cities and regions working to renew themselves. For example, they realize they must attract young people and make everyone feel welcome, regardless of background, political views, orientation, etc. They discuss the need for truly engaged citizens, who don’t just “consume” what the community has to offer but who feel a sense of responsibility for it. And they zoom in on the collaborations between institutions and also small businesses that create a lot of synergy and trust.

You’ll be interested to hear about the upcoming HBO documentary based on James’s and Deborah’s book. And you’ll be uplifted by their optimistic mindset: while America is surely going through a hard time now, we’ve been through many other hard times before. We can achieve renewal and reconstruction. It is up to us to make it happen.

James and Deborah will also speak at EntreCon, our virtual business and leadership conference held Wednesday and Thursday, November 18 & 19, 2020. Click here to register.

Quint Studer

Well, it’s so exciting for me to have Jim and Deb fallows here on my busy leaders podcast. I met Jim probably a year and a half ago or so and you know, in our search here in Pensacola, civic Khan, for those of you who aren’t aware of civic Khan, it stands for civic conversations. And we bring in truly experts from around the country to share best practices. And Jim was nice enough to come. And Deb, you had a family emergency that trip, you couldn’t make it.

Deb Fallows

But he continues.

Quint Studer

Um, yeah, well, we probably might have something in common there. With my 95 year old mother lives next door to us. So I’m a fish all the time where I go, but, um, but Jim talked about you all the time. And so it’s so great. So great to have you on the podcast because I understand I can tell what a team you two are. And that’s well, really marvelous.

Deb Fallows

Thank you. I was so sorry to miss the trip to Pensacola. My mom is in Florida. I was so so near and yet so far. And Jim talks about Pensacola all the time, I feel like I’ve been there. And they say, yes, Jim, I get it, I get it.

Quint Studer

Like what my own. So you know, I spent a lot of years traveling from hospital to hospital. And when you see some of them just doing some great things you get really excited about because and you want to share it, because you’re just trying, you’re not trying to make one town great. You’re trying to make all times Great. So those of you that I know, you’ve already heard a lot about Jim and Deb. I’ve got their book right here in front of me, our towns are 100,000 mile journey into the heart of America. Um, and when you were, Jim, when you’re traveling on all these little towns, seeing what you were seeing, when you first started the thought of doing this what what encouraged you to say, Hey, I think I’m gonna travel all these little towns. I mean, well, what what caused you to think about doing it either.

Jim Fallows

So in the beginning, it was just a journey of exploration, mainly because we’ve been living in China for a number of years. And we travel all over the extent of China and reporting for the Atlantic. So we came back to the US to our home in DC, we thought, why not also explore some of the extent of the US to see cities that we didn’t usually see on the evening news, or, and then the main papers. And I think we thought this would initially just be a short couple city venture, I went to Sioux Falls, South Dakota first, and then Holland, Michigan, and then Burlington, Vermont. And as we started to see patterns, it was just so impressive and interesting, and things that we had no idea about. And we thought most people didn’t have an idea of what was going on beyond their own borders, we started to see patterns. And so just the the exercise for us over the next four years, basically from 2013, to 2017, of learning about what was distinctive city by city, and what was in common in cities that were on the way up, that was what kept us going. And it’s why, among other things, we’ve been telling the story of Pensacola and civic con and what you’ve been doing in other places we’ve been because there are some patterns of recognizable success, you can see in cities and regions that are trying to renew themselves.

Deb Fallows

And at the very beginning of this, it was just it was poster session around 2009 2010. And we had been in China for several years before that, and felt a little bit out of touch of just what was happening in the US. So we we wanted to visit some towns that had maybe have a story to tell that there was something compelling about them. And particularly if they’d had a some kind of a shock happen, like the mind closed or the mill or the factory closed door, or if there was a big demographic shift going on, or whatever it was. So Jim put an item on on the Atlantic, where he has a pretty big following and leadership saying we’re going to undertake this journey. And what about your town? Do you have a story to tell in your town? Should we Why should we come to your town. And after about a week we had more than 1000 responses from people. And it wasn’t just here’s my town. But it was these long, heartfelt essays about what to do. So we thought at that point, that maybe we were onto something that there were a lot of towns that had a lot of things going on. And we just we started going to a few of them hit or miss or where we knew one or two people and then went on from there. And just one other point was that we were going to rather smaller towns, which felt felt good to us for a couple of reasons. One is that we both grew up in small towns, Jim’s from Southern California, and I’m from Ohio, a town of 10,000 on the lake. And so being in a small environment where we felt we could spend a few weeks or return trips at a time and get a sense of things and it would be in a context that we knew from growing up in places like that too. So that was kind of the background and setup for how we started traveling.

Quint Studer

I love that you know I got sort of turned on to this work by accident. I was told Talking to Jim Clifton, President chairman of Gallup Corporation about health care, because he wanted to talk to me because he noticed that the time companies that I work with that Studer group, when I owned it, did better hospitals did better than others. So he just wanted to know, what were we doing with these hospitals and made a difference? And he mentioned to me, they had done some research on what differentiates communities that thrive, and those that don’t. And then in my travels, I just started, you know, how you don’t notice something or hear something? It’s like, there’s a speaker I know that says, count yellow cars. And I think, why don’t we even see a yellow car, but then after that, I’m looking at yellow cars everywhere, once I become aware of it. So so what what what were some of the pickup things? What did you notice about some of the cities that were maybe having more success? Because a lot of small communities, I find, came up with reasons why they couldn’t, because it’s hard. So what what are some of your findings in your book,

Jim Fallows

so some of them, which we were telling anecdotally through through our travels, and then through a kind of summary chapter at the end, I’ll just just illustrate a couple of them. One is the presence of people who we described as civic patriots of people who decided felt as if they had a responsibility to their surrounding area. It wasn’t just some place they lived. It wasn’t some place that they just, you know, consumed the goods from, but it was a place they felt some responsibility for. And there was one of our travels, we got a very interesting note from somebody who had worked, I believe, for Google, in the Bay Area, San Francisco and decided to move to a small town in Texas. And he said, if you want to consume a great community, you can live in someplace like San Francisco or Cambridge mass or something. But if you want to create a great community, you can come to some place like the city that he and his wife had moved to. So the presence of people who you could identify as making things go often in our our inquiries, we’d ask people who makes things happen here? And the answer is varied. But the fact that there was an answer was a very important thing. We found I’ll just mention two other things on the checklist. One is a kind of institutional experimentation, we would ask people, what are the interesting schools here, what’s happening in the community college, what’s happening with the library, what’s happening with the Arts Commission. And if you found places where cities were doing interesting things, in those regards, that was also a good sign. I’ll mention one other, which is we found lots of cities that were intentionally making themselves open. They realized that in the long run for a city to grow, it has to attract new people has to convince young people growing up there to stay. And people have gone to other places, there’s a place to live. So taking the steps to make people of different backgrounds, different ages, different political views, different orientations feel like this could be there place. That was also a common thread we found and microbreweries too.

Deb Fallows

And another thing we found, Jim mentioned the institutions in town was when when you could, you could see the networking going on, you could see the collaborations going on whether it was at a high level, like public private partnerships, or whether it was at a at a much more micro granular level, like several shops along Main Street getting together and having a common evening out, you supply the beer you supply the Sanchez, use apply the music, that that kind of knitting of a big fabric in it in a tighter weave, where people not only knew each other, but they knew how to work with each other. And it created a kind of synergy and trust, where if you had a problem, you knew to whom you should go, if you had an idea, you knew who was going to be receptive to that idea or not, it just that the kind of human context of instead of the institutions getting together, because, you know, the people and and i think that also spilled over into, into the sense of leadership and, and personal participation. If you live in a town, you know, it’s up to you to to, to help build that town. And you know that you have to kind of behave well with the other people in town because you’re going to see them when you pick up your paper every morning or at the grocery store or at the school meetings. So it’s it’s bringing those big levels on to a smaller level where the more people you can get to participate, the easier it is to kind of go over the bumps that you will run into and create the the new space for things that aren’t there yet.

Jim Fallows

And Quint. Could I interrupt and add one more thing to what Deb is saying? Which is that Just briefly because it’s connected to Pensacola to that the skills of leadership and involvement aren’t things that people just intrinsically have. And so communities that invested in teaching these things and creating the networks in South Carolina is a statewide Leadership Network and Knoxville, there’s a huge community network. Of course, you all have sivakasi. So that idea of people don’t know how to drive a car unless they’re taught, they don’t know how to ride a bike unless they’re taught. And being part citizens is something that people can be can become better at, too.

Quint Studer

I love what you said, You know, sometimes, when you hear somebody explained it, you realize what you experienced, but you didn’t know your experience. And yeah. And I went to Asheville early on, because I heard I should go to Asheville. And I was sitting down with Pat Whalen, who was one of the big players there. And I just was thinking, well, who made this happened? So of course, I asked about government. And he looked at me and said that this is not about government. He said this is about local, private people taking ownership of their community and controlling their own destiny. And what it hit me is, it’s easy for me to be a victim waiting for someone else to save me, someone else to fix it, someone else to bring the solution. And the message I got from Asheville is you can make this happen. But you’ve got to not you got to quit looking for somebody else. It’s you know, not when I’m not saying knee, it’s people in the room. And the other thing which I love about the way you’re talking is it’s obvious these people you met love their community. Yes. And they have for their communities is really, really remarkable. So So now you publish the book. And of course, when when you publish a book, you sort of learn all sorts of things after you publish the book. You’re lucky because you do this. So well. I’m the type that people actually send me my book and tell me I misspelled a word here or there. I should have said this. So So you’ve been other places since then, is there any any new learnings or learnings that maybe went a little bit deeper?

Jim Fallows

So So I will, I’ll give you a boring high policy point then devil tell you about what she’s been learning in South Dakota, where she’s got an honorary South Dakotan, I think the two main things we’ve learned in the kind of probably the 40 or 50 places we’ve been since the book came out, as opposed to the 40 or 50. We’re doing a bit bit longer writing the book is, number one, how widespread is this movement of civic involvement that, that we had no idea that Indiana, they’re all they’re these urban renewal efforts in Fort Wayne and that, for example, in Muncie, Indiana, Ball State University has taken over control of the public schools in in Muncie, because they thought that was a way to have them be effective. And public arts programs help app happening over the place, you know, in Tulsa, for example, which is its own story. So number one is, how broad is the extent of this nationwide movement that doesn’t yet realize it’s a movement. So that was one big understanding. A second one is how I think there’s a it’s a historical moment of connections and patterns. There’s lots of people doing similar things in Fresno in, you know, Rapid City, South Dakota, and you know, Bentonville, Arkansas, and Pensacola and dozen other places who don’t realize their part there. They could be learning from each other. So the importance of the connection to something we want to do, I guess another is an emphasis on local journalism, that local journalism is a very important part of this matrix, and finding ways to keep it going. I would say those are three things that I have learned.

Deb Fallows

And, and I have learned those things too. And also learned a couple other things. And it you know, it’s hard right now to separate a timeline in your life of before and after the Coronavirus and the lockdown and all of the changes in life. And everything looms so large to me since March. And I feel I’ve learned a tremendous amount about what we saw in the community since then, in a funny way since we can’t go out and and visit anyone. I’ve been on these zoom calls with the State of South Dakota at least twice a week since March. And it’s it’s a group that’s run by the Economic Development Group statewide and people from communities all over the state Collin they’re probably a couple dozen of them. I I feel I know all my neighbors there now I’m like an honorary citizen. But today I’ve learned from the last six months about all these issues we’re talking about of the importance of the local are a new sense of urgency. We talked about how it’s up to you, you’re going to have to do it yourself. But it feels like that is much more important now. Because it’s just such chaos, and nobody can wait for anything to happen. If you’ve got, if the schools are closed down, your community has to fix it. If there’s a red rally in Sturgis, where 10s of thousands of people are coming on their motorbikes. They’re coming no matter what. So we have to be prepared for that. If you know you name it, if you’re having trouble with a small businesses, it’s happening here. And now. So we have to address it. So I think that sense of urgency is, is one thing that I’ve noticed. The other thing is how, how people want to move along the process of learning how to fix their towns, whether it’s in times where you’re flourishing, or now where it’s when it’s in times when you’re having trouble. It’s turned to a much more practical sense of well, how do I do that? You know, you guys in lemon, South Dakota, tell me how to fix the small businesses where we’re having trouble in in another city, tiny city in South Dakota. So I think that that the learning from each other in very practical ways where I, I hear a lot of talk about Okay, you know, you’re talking about toolkits, and you’re talking about best practices, and you’re talking about how tos. But give me the list of what am I supposed to do when we’ve got all these new people coming from the cities, which means Minneapolis and St. Paul, or other parts of the country? And they want to they want to settle down for a while in our small town in South Dakota? Because it seems safer. It seems less expensive, it seems more protected. Do we want them here or not? You know, we don’t even have enough food in the grocery stores to sell to these people. But we don’t want to we don’t want to send them away. We want to, we want to take this as an opportunity. So what do we do? For example, when somebody comes and says, look, I think I’d like to settle here. I’m an entrepreneur, I’d like to, I’d like to start a bakery. Great. We’d love to have that bakery. We’ll help you figure it out. But then, what do we do with the guy down the street, who already has the bakery, we love him too. And we don’t want to hurt his feelings, which is more important maybe in South Dakota is in some other places. But these very practical issues that that people are talking through in times of stress that they might not, not talk through and times of flourishing,

Quint Studer

but I’ve never had to talk about it because they weren’t flourishing.

Deb Fallows

That’s right.

Quint Studer

Minnesota nice is moving into South Dakota.

Deb Fallows

And they’re plenty nice. So it’s, it’s a lot.

Quint Studer

Now that goes through that too. And I think that’s a part for every city to get over the hump. Like that, that restaurant that is scared there, the second restaurant, then it comes in and they find out it works. But that that anxiety until it happens and, um, yeah, I love the fact that you got, you know, both that local local solutions, local answers, and, and how do you do it and, and wanting to learn from each other is just marvelous. So as we move along, and I want to cover a couple other topics I want to cover you’re going to be a doctor con both of you, hopefully, and we’re thrilled to have you there. Deb, we’re very thrilled to have you there, you know, and and when Jim walks into the perfect plane, and they immediately recognize him, I don’t think he was in the craft beer place all that long. Um, tell me what you’re going to talk about. Because you know, for the first time ever an entrepreneur, we have a community trapped, because they all didn’t having a healthy community having healthy small businesses you fit. So we really excited about having a community track and we’re just absolutely thrilled that you endeavor are part of that. What What do you think people are going to hear from you when you talk to them?

Jim Fallows

So I think the main thing we’re going to talk about is the time ahead. As we’re all speaking here, the country is being distract. I mean, there is a political, you know, event going on in the us right now in the form of a presidential election, which is consuming a lot of emotional energy from everyone that that will pass. And of course, we’re having an economic stress on the entire country, entire world and in a public health. You know, crisis not seen in a century, but these things there will come another time. And I think that the ground is being prepared for something probably Next year, regardless of the outcome of this election, I think a lot of new things will be coming in terms of coordinated national, statewide and local efforts to rebuild the things that have made lots of local America flourish over the past decade, I think there’s going to be I’ve heard from lots of people around the country about new measures, new connections, new emphases, that to prepare people to come out of this stress, economic, medical, emotional, political, that everybody in the country is feeling right now. So I think mainly, we’re going to try to talk about what is a head? And how to take advantage of what is the head?

Quint Studer

Oh, that’s marvelous. Let me ask your question. And Deb, you can tell us about the hbo movie, I wasn’t going to talk about it. But before you got on, I got so excited about it, about how the movie came about when it’s going to possibly premiere and what are people going to see?

Deb Fallows

Oh, gosh, this has really been an experience. We’ve been incredibly fortunate that HBO came to us and said that they they were interested in doing a documentary that was based on the book, and to our great good fortune. They connected us with a wonderful team of directors. It’s a couple about our age, and named Steve Asher and Jeannie Jordan, who are longtime directors of documentaries and producers. So we worked with them for about a year and a half, and chose half a dozen of the towns that we had been to and, and all found interesting, beautiful, geographically different different kinds of stories to tell. And we spent how many days 100 days